Please welcome Booktrope author and speaker Daryl Rothman. Daryl has a great post on flash fiction, a really neat form of writing. Without further ado, here is Daryl.

What’s in a word?

Quite a lot, it so happens. What’s in a novel? This varies but it’s safe to say, pending genre, at least 50,000 words, and usually more. My debut novel will check in between 75,000-80,000, and that’s after lopping more than 20%. For most authors that tends to be a painful but ultimately essential process, one which underscores the critical importance of making every word count.

Maybe not as acutely as with poetry—where every word, letter and even appearance on the page is paramount—but then again, why not? Would any writer worth her salt really be okay saying certain portions of her manuscript can just be meh? I hope not. The challenge becomes, how to lend to one’s writing and editing—no matte the genre or form—that same crucial vigilance?

Like many of you I’ve read countless articles—many of them good—offering tips on how to create lean, compelling prose. But I am going to talk about–briefly, as would seem to be warranted—something that has been a revelation for me.

Flash Fiction.

Sometimes called micro fiction, it is an abbreviated form of prose not typically exceeding 1000 words, often curtailed at 500, and sometimes even 150 or fewer. They are stories, with a beginning, middle and end, though not every practitioner suggests that order. But this is not a primer on flash fiction; most of you are probably familiar with the essentials.

What this is, rather, is an explanation of how and why flash fiction has transformed my writing, and how it can do the same for you.

Dan Quayle once said, “Verbosity leads to unclear, inarticulate things.” To wit. I would be remiss if I didn’t confess my own tendency toward floridity. Improvement is not always just a matter of shortening things—though often that is part of it—but involves finding the most crisp, effective manner in which to say something.

As Elmore Leonard said, “If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.” Sometimes I write insecurely—that is to say, I become preoccupied with wanting to show how well I can write. This invariably ends badly. You don’t want to watch a movie thinking, wow, this is really great acting. You want the acting to be so good that it carries you away and only later when you reflect upon it has you marveling at the performances which made that possible. With a book, you want the writing to be so good—the story so compelling—that the reader loses himself in it, rather pausing to think about the writing itself. (Now, the writing better be good, or the reader will be contemplating it in ways you would likely not prefer.)

Flash fiction, properly wrought, leaves an author no choice but to write crisply and effectively. It requires a laser-sharp precision and thorough distilling process in which excess is trimmed and only pure flavor remains. There are some great resources and examples, but to avoid mucking around with someone else’s work, permit me to touch upon a short piece of my own.

I was honored that the great folks over at The Hoot published one of my flash pieces. It’s a brief retelling of an actual interaction with my two youngest children, and conforms to the publisher’s 150-word maximum. But not initially; the first draft—and this is almost always the case—was too long and not nearly refined to sufficient quality. I am not saying it’s a masterpiece—I am, quite simply, illustrating something of my writing process when working in this form.

In case you didn’t click the link, here is the piece:

Requiem for a Mouse

Vexation!

My mouse is dead and my work stalls and my children, one six and one three, hear my lamentations and come running.

“My mouse is dead,” I tell them, abashed over my dramatics but they are children and they are love and their eyes full of concern and ideas and they toddle away in different directions. Some minutes later both return with items in hand.

“Here you are, Daddy,” says the older, extending her hand and placing a battery in mine. “To bring your mouse back to life.” I smile in thanks and muss her wavy hair but the younger child pushes his way to me and extends his little hand as well. He has brought me a small, empty box which once housed small toys.

“Your mouse won’t come back to life,” says he. “But here is a box, and you may bury him in our yard.”

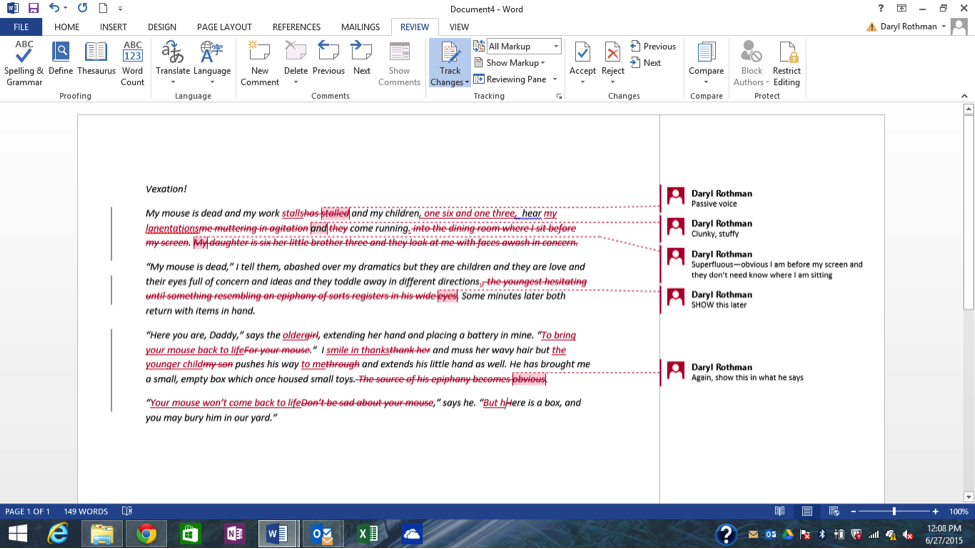

Again, far from perfect but a fairly lean little story which gets to the heart of that silly but poignant moment with my kids. But it took a little polishing to get it there. The first draft looked something more like this:

Vexation!

My mouse is dead and my work has stalled and my children hear me muttering in agitation and they come running into the dining room where I sit before my screen. My daughter is six her little brother three and they look at me with faces awash in concern.

“My mouse is dead,” I tell them, abashed over my dramatics but they are children and they are love and their eyes full of concern and ideas and they toddle away in different directions, the youngest hesitating until something resembling an epiphany of sorts registers in his wide eyes. Some minutes later both return with items in hand.

“Here you are, Daddy,” says the girl, extending her hand and placing a battery in mine. “For your mouse.” I thank her and muss her wavy hair but my son pushes his way through and extends his little hand as well. He has brought me a small, empty box which once housed small toys. The source of his epiphany becomes obvious.

“Don’t be sad about your mouse,” says he. “Here is a box, and you may bury him in our yard.”

Not dramatically different, but thirty-nine words (26%) over the limit, and flecked with excess. So, I went back in:

This wasn’t rocket science. And to be perfectly honest my initial focus was simply finding ways to reduce the word count. It was almost like editing a tweet down to the 140 characters. This might at first seem an arbitrary exercise in parsimony, but you’d be surprised at just how vigilant this forces you to become: when already constrained within an abbreviated platform, it becomes even more critical to preserve only the right words. Did I accomplish this in the piece I shared? Not perfectly. I improved it from the first draft, but looking now I could sharpen it further still. It’s probably not necessary to know my daughter’s hair is wavy. Lamentations is a bit over the top. I could purge the part about the concern in their eyes. There was concern but the main thing was to show it through their words and actions, so that could have hit the cutting room floor if necessary.

It is this very process—a more grinding than revelatory one—which, practiced consistently becomes a revelation. A repetitive vigilance wherein I seek to retain only those materials necessary to sculpt and chisel a clean, polished creation. And both things—the paring and the sculpting—are necessary. It is not merely a case of trimming things down to the requisite word count. That’s the perfunctory part; the magic lives in finding the right words, and the right order for them(this latter consideration can play out very differently in flash). I’ve a tendency to edit a novel with something of a 30,000-foot view, improving things best I can but sometimes succumbing to the fallacious notion that I don’t need to scrutinize every single word because the damn thing is 300 pages long, after all. I can edit in the context of those 300 pages and probably be okay, so long as I’ve crafted a good overall story at the end of the day.

Ah, but what better way to ensure a good—and hopefully great—story than to avoid the pitfalls of such thinking? That is where the focus and vigilance exacted by flash fiction has been a game-changer for me. Reading flash, like reading poetry, is like peering through a magnifying lens: each word and even the arrangement of words is of terrific import. Good flash and good poetry must be crafted with that magnifying lens in mind. When you have only a few paragraphs or even but one in which to tell your tale, every word counts. So why not extrapolate this approach to longer works too? If every word counts in even one paragraph of flash, and words and paragraphs are, after all, what books are made of, then all the more reason to remember this approach.

So what do you think? Have you tried your hand at writing flash fiction? Do you have a favorite flash author? Thanks, and whatever your bag, as Austin Powers might say, happy writing and reading!

About Daryl Rothman:

Daryl Rothman’s debut novel is being published by Booktrope in 2015. He has written for a variety of esteemed publications and his short story “Devil and the Blue Ghosts” won Honorable Mention for Glimmer Train’s prestigious New Writer’s Award Contest. Daryl is on Twitter, LinkedIn and Google+ and he’d love you to drop in for a visit at his website. Daryl is not sure why he is speaking of himself in 3rd-person. And, like George, he likes his chicken spicy.

Daryl Rothman’s debut novel is being published by Booktrope in 2015. He has written for a variety of esteemed publications and his short story “Devil and the Blue Ghosts” won Honorable Mention for Glimmer Train’s prestigious New Writer’s Award Contest. Daryl is on Twitter, LinkedIn and Google+ and he’d love you to drop in for a visit at his website. Daryl is not sure why he is speaking of himself in 3rd-person. And, like George, he likes his chicken spicy.

I’ve heard (or read) that really good writing is “transparent”. The reader doesn’t even notice it, all he or she sees is the story. That’s what I strive for.

Well-said, Brant. I strive for it too. Don’t always achieve it, but I do better when I remember some of those suggestions in my post.

Thanks and best wishes!

Wow. That’s neat. I do this too, particularly when the words cease to flow on my own stories. It’s a nice way to get out of my own way. I don’t think I have it in me to write a 150 word story though.

Thanks Kelsey. It’s ok if you don’t , but I didn’t think I did either…you just might be surprised. And how about those 6-word stories? Whew!

Best wishes!